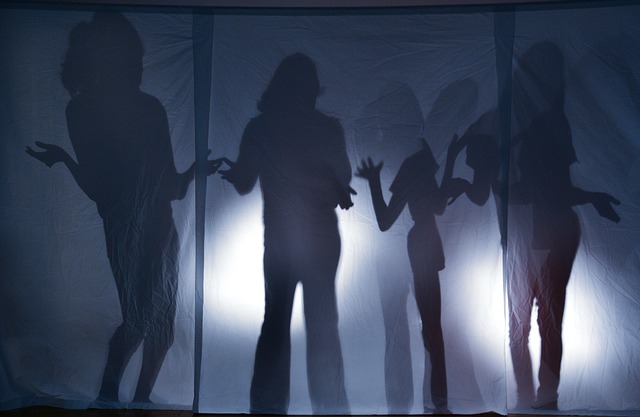

The Ambiguity Zone

A reader of this blog recently left a comment on social media, one which I think is worth exploring a bit:

“What I think about a fair amount is that time period when everything is ambiguous. You can’t tell if its Katy bar the door all hell’s breaking loose time or something less that requires more restraint.”

His comment was specific to self defense scenarios, but I think it applies regardless of the event timeframe; I saw it in action during the run-up to Hurricane Dorian this week.

It’s also, I think, a much bigger topic than it appears.

How people handle ambiguity is (among other things) a function of their awareness of what danger is; the information they have about the situation; their understanding of their response options; their training or rehearsal for those options; and, perhaps most importantly, their willingness to face reality.

I’m going to start with that last one, because it’s key to being able to handle ambiguity.

“This can’t be happening”

Many years ago someone told me that you either acknowledge reality and use it to your advantage, or it will automatically work against you. A vital part of preparedness, whether we’re talking natural disaster, criminal attack, or any other potentially life-altering event, is considering the reality of the situation.

Reality is the way things actually are (or are likely to be), not the way we wish them to be. Most people, I’ve observed, believe they’re completely rational — that they always look at facts without passion or bias.

The reality (see what I did there?) is that most people look at events through the lenses of their pre-existing beliefs, predispositions, hopes, and especially their political persuasions. Those things affect the decisions they make.

For instance, someone who believes that all people are inherently good may not be able to face the fact that they’re being attacked. Someone who believes that the President (regardless of which one) is doing an excellent job may not see the indicators of an imminent and severe recession. Someone who believes that vaccines cause autism probably won’t see the dangers of re-emerging diseases. I’m sure you can come up with others.

An inability to face reality means that, during the ambiguous phase of any impending event, the small (or large) clues which indicate the most likely course of events (and the best response to that course) will be missed — or even actively ignored. It’s difficult to impossible to process information if one’s eyes are closed to the conclusion.

I’m positive that negative things happen

I understand this tendency all too well. Though my sometimes gruff exterior would suggest otherwise, I’m actually an optimist; I have a tendency to believe that everything will work out for the best. Experience, however, has taught me that it doesn’t always happen that way, and particularly so if I don’t do something to ensure a positive outcome.

This predisposition to optimism is common, and in most cases I think it’s a positive character trait. There is such a thing as being TOO positive, however, when it results in a disbelief that things could be any other way — or worse, in not wanting to even acknowledge that bad things often happen to good people.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus — and a Jason Voorhees, too.

The first step in successfully navigating that ambiguous moment, then, is to understand that bad things do happen and it could be happening to you, right now. This is where studying previous incidents, whether they be criminal attacks or natural disasters, is valuable. Seeing what has happened to others, and how they reacted (successfully or otherwise), is a good step toward facing reality.

It’s not complete, however, until you can internalize it to your own life. It’s very easy to think that such things only happen in “bad” neighborhoods, and since you live in a “good” part of town you’re safe. That’s not realistic; while bad things can be shown to happen more often in certain areas than others, some percentage of those things happen in other places. It’s THAT percentage which is the reality you have to face.

There is a caveat here, however: don’t allow yourself to become obsessive about this kind of study. The result can be creeping paranoia, that you’re in more danger or face more risk than you really do. That’s not realistic, either.

Balance, then, is the objective. To successfully get through the ambiguity zone you have to understand what you might actually face, acknowledge that there is a good chance you’ll face it sometime during your life, and be proactive about protecting yourself from it. At the same time, know that nothing is certain and don’t letting the anticipation of that danger hang like a cloud over you.

But how does one choose a proper course of action when the signals aren’t clear? We’ll look at that next time.

-=[ Grant ]=-

Listen to this blog – and subscribe to it on iTunes by clicking this link!- Posted by Grant Cunningham

- On September 6, 2019