A new way of looking at likelihood and plausbility

A couple of decades back I started to talk to my defensive shooting students about the likelihood of being attacked and needing to use their firearm to defend themselves. It seemed to me that some people, based on their lifestyle and habits, were more likely to need to use lethal force than others.

It also seemed to me that, even when the defensive firearm was actually needed, the mode of employment varied greatly; sometimes the sight of the gun itself was enough to scare the attacker away, while other times the only resolution was the physical incapacitation of the suspect.

Finally, both of those made some shooting techniques (skills) more likely to be used than others, and I came to the conclusion that the expectation of use should be factored into training and practice in some way.

At the time, most defensive shooting instructors taught all skills as being equally important, as equally likely to be needed. We didn’t have good data as to how defensive encounters really happened, and we gave too much weight to first-person accounts of incidents.

Today we know that memories, particularly of traumatic incidents, aren’t recalled so much as they’re reconstructed by our fallible minds. Today we also have a great quantity of surveillance videos where we can actually see what happens, making our analysis much easier.

While some still resist the idea, the reality is that some things happen more often, and are more urgent, than others. The modern approach is to train in those things which are more likely, and not waste our valuable training resources on things which aren’t.

But how do we judge likelihood?

Sometimes simpler is better

I’ve wrestled with this idea for a long time. Over the years I’ve used several approaches to explain how to judge which events were more likely (and figure out which skills/tools were more likely to be needed). If you’ve read any of my older books or taken one of my classes you’ve encountered at least one of those explanations.

The only trouble is that I’ve never been happy with any of the explanations I’ve used. They were either difficult to explain or required too much analysis and segmentation on the part of the student. It seemed there should be an easier way to explain the idea and, at the same time, give my students and readers a tool to quickly judge what they’re doing (or are being asked to do.)

That tool, I believe, is the Plausibility Line.

States of expectation revisited

If we take the universe of things that could happen, in the sense that they don’t violate the laws of physics, some things happen more often than others. Some things happen less often than others. Some things really don’t happen at all, even though some people may be convinced that they do. Finally, some things are never going to happen except in the imaginations of Hollywood writers!

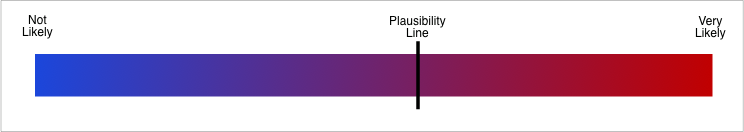

This likelihood, this expectation of occurrence, is a continuum — less likely things on one end, more likely things on the other. The point at which something could reasonably occur, because it has some history of happening or because it’s the result of a combination of other things that have happened, is the Plausibility Line.

The Plausibility Line separates those things which really don’t happen (or don’t happen often enough to justify the expenditure of scarce preparedness resources) from those things which do. The Plausibility Line is where things begin to occur, where you can judge something to be important enough to worry about.

The Plausibility Line is where you judge whether something could rationally, believably, happen to you or your family. It’s the incident which you should be concerned about or the skill which you should probably train in or the gear you should add to your preparations.

The Plausibility Line in action

The closer to “Very Likely” the incident or skill is, the more important it will probably be in your preparations. The further toward “Not Likely”, the less important it is. The demarcation, the point at which you decide to do something about it, is the Plausibility Line.

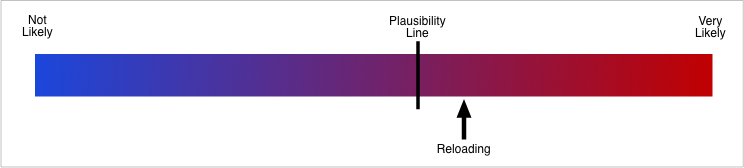

Let’s take a skill all of the defensive firearms folks in the audience will understand: reloading the gun during a fight. The reality is that it’s difficult to find incidents in the world of private sector self where a reload was needed during a defensive shooting, and rarer still to find one in which the reload affected the outcome of the fight.

Still, reloading does have some small historical basis. With the increase in crimes involving multiple attackers, and the prevalence of low-capacity sub-compact pistols and revolvers, it’s possible that the combination might result in reloading being a more plausible skill.

If I were to place it on the likelihood spectrum, it would probably fall here:

It’s not something which happens often enough to justify specialized reloading drills during practice, but does justify learning a good technique and then using it during other practice when your gun runs out of ammunition. It’s a plausible skill to practice, but it doesn’t rise to the level of a critical skill because it just doesn’t happen all that often.

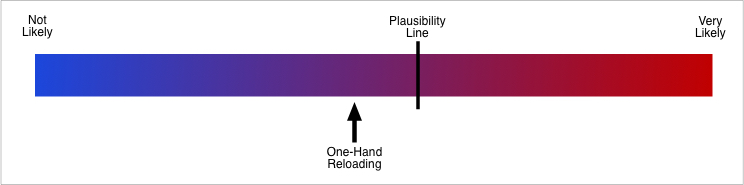

So, if it’s hard to find cases where reloading the gun was important in a self-defense encounter, how likely is it to need to be able to reload with one hand only? This is a skill that’s taught in a lot of “advanced” shooting courses, but frankly I’ve been unable to find even a single incident in the private sector where it’s been used. It’s just not a skill which is believably necessary.

On the spectrum I’d put it here (and I believe I’m being quite generous):

As you can see, it’s firmly on the other side of the Plausibility Line. Things that fall to the “Not Very Likely” side of your Plausibility Line are things you probably shouldn’t be wasting your time, energy, money, or interest on — no matter how intriguing or sexy they may be. One-handed reloading is certainly that, and it’s something many instructors spend a lot of time on instead of other, more important, skills that will actually keep their students safer.

Such is the power of seduction when one doesn’t understand the notion of plausibility and why it matters.

Do your own evaluation

If someone is selling you something that falls close to your Plausibility Line, you should look at it very critically. Just because someone says something is important doesn’t make it important to YOU.

This isn’t just about self defense, either. If you’ve read my book Prepping For Life, you’ll know that this idea applies to preparedness as well. Some events are more likely to happen than others and thus should command more resources (in the form of time, money, or attention) than others.

For any skill, for any event, for any piece of gear or other acquisition, ask yourself: which side of my Plausibility Line does this fall? If it’s on the “Not Likely” side, don’t waste your time, money, and attention. Instead, find those things on the other side of the line and spend your resources there.

That’s what will keep you and your family safer.

– Grant

P.S.: Thanks to everyone who attended my Threat-Centered Revolver class in Texas over the weekend. We’re hoping to put this class on again next spring, so if you’re anywhere near northeast Texas keep your eyes open for the announcement!

Listen to this blog – and subscribe to it on iTunes by clicking this link!

- Posted by Grant Cunningham

- On May 21, 2018